Gaining a critical perspective on AI use during engineering processes

Welcome to this opportunity to use one of those mysterious AI tools to gain knowledge!

Here, we will focus on gaining a critical understanding of an AI System generative AI System large language model-based tool. Why the strike-outs in the previous sentence? Well, when we talk about AI systems, that could mean a lot of different types of systems that are good for different purposes, so we will try to be specific and have you be critical enough when hearing of/engaging with AI systems that you remember to ask ciritcal questions:

- “What does ‘AI’ mean in this context?”

- “What are the limits of the use of a particular AI system in this context?”

- “What knowledge or information does the AI system use, or what data was used to train the AI system?”

Instead of blindly using an AI system because it “looks cool” or gives a “cool response”, we want you to think more critically about it. We know you can stay cognizant and stay ready to be critical and inquisitive, because you’re engineers! If you’ve ever heard the phrase “debbie downer”…

…well honestly that might be what you have to be sometimes. But thats the responsibility that can come with expertise!

A little background

Unfortunately, many modern AI systems are very opaque and the companies controlling those systems may make answering those questions very difficult. When we can’t answer basic questions like those, it gives an opportunity for the Critical Engineer you should want to become to assess whether you want to use a particular system and whether it is the responsible thing to do.

Values and context are important for thinking about responsibility but folks like Dr. Chris Dancy and Timnit Gebru (who’s pictured below) have written quite a bit on perspectives of responsibility in using AI (and now generative AI) systems. Give “How to use generative AI more responsibly a quick read for one perspective on using generative systems responsibly (though this is slightly contextualized for psychologists and cognitive scientists, the majority of these lessons apply to engineers as well!)

This is all to say that as engineers, you will have a choice in what AI systems you use at tools and how you choose to use them! As folks who engineer artifacts you will likely want to be able to tinker and understand the systems you are using. Some AI systems make that easier than others.

Large Language Models

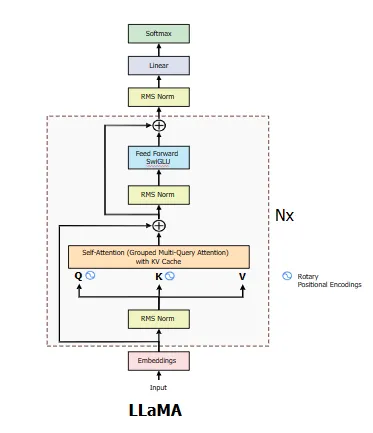

We are going to explore the use of one particular kind of generative AI system called a large language model (LLM). Large language models are machine learning models that typically use a series of neural networks (with a particular transformer architecture). Here large represents the number of parameters, which these days will be in the billions for the more popular LLMs. LLMs essentially output sequences of text (and sometimes other types of media) based on some input text. We’d note that they do not understand, they complete (text) sequences with an output. They do not have human-like cognitive processing of information, but these systems certainly can output information that matches the input very well. The details aren’t too important for us, but if you want to learn more, there are both resources out there and classes here at Penn State that will cover some of the basics. Dr. Dancy spends a few classes going over the transformer architecture in his AI, Humans, and Society class, for example!

In this learning module, we are going to go over using a particular LLM, MEP-NEO. We chose MAP-NEO for a few reasons, but two main reasons is accessibility of the model building code (particularly thanks to a platform called Hugging Face) and transparency of the model (the creators of MAP-NEO give architecture detail as well as tell us what data the model was trained on). Accessibility also means that more people can tinker with the models to try to make it their own and fit within their own contexts, something that can be very powerful and impactful (responsible use & development is still important!)

These two points allow us to bring the model to you in the learning module in the way we do and that is much more open that popular systems such as chatGPT (which, beyond the company behind it not being transparent about how the model works or what data is was trained on, is implicated in paying workers a very low wage for data work necessary for the models functioning.) The system we use is called Llama 2, which was released last year. While there has been a newer version of the model released this year (Llama 3), the developers (Meta) hasn’t yet released information on the data used to train the system, so we’re sticking to this version for now. (Even version 2 works fairly well!)

The MEP-NEO models come in several variants, all of which are reltively small when compared to typical LLMs! Thus, we’ll use the biggest variant - 7B (for 7 Billion parameters). Though this is the bigger of the MAP NEO models, it’s the size of what has been typically the smallest variant of recent models. Why do we use a smallest functional version of an LLM? (Take a second to think)

If you guessed because of how much space it takes up on a disk/hard drive, then you would be correct! But that’s not the only reason we would consider in computational system to use something smaller. If you also guessed because of how long it takes to run the model (i.e., speed), then you are also correct!

When we say speed, we are specifically talking about how long it takes the model to give output given some input, what we’d call an inference. This is because the amount of parameters basically tells us how many computational functions we’ll need to run to eventually get to an output (we won’t go into the math and architecture here) - typically the more parameter, the more computational functions we need to run.

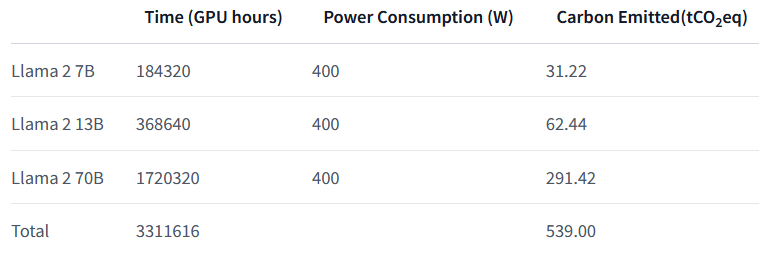

So in the normal chatbot example (and we’ll be interfacing with a form of chatbot here soon) the input is what you right to the chatbot and the output is it’s response. The other big aspect of speed related to these models (but which we don’t have to worry about directly) is how long it takes to train the model. If you go to the model card for the Llama 2 model on HuggingFace (for example), you’ll run across the table shown below:

The important take-away here is that training incurs a cost in time and in the amount of carbon emitted (read: polution), so the size of model you decide to train matters. While one instance of model inference, is much “cheaper” than training, you can imagine that inference actually ends up being where the most environmental impact occurs, with queries (input-output requests) from millions of users happen in a short amount of time. So, the smaller model you can use to accomplish a task, the less space, time, and environmental impact you will likely have.

NOW if you’re asking, “well why are we even doing this, then?!? Can’t we just not use the systems?”

Well, yes and no. You can not use the systems, but there’s a good chance you will given the ubiquity of these systems and when you do we want you to be able to think critically about that use. So we’ll try to give you some knowledge and experience here, but leave it to you to gain the expertise you need throughout your educational journey. If nothing else, we’re here to make your life more difficult so that you can’t just do things out of ignorance.

Now that we’ve given a high-level view of why we’re doing this and a little background, let’s move on to your MEPO, design challenge specifics.

The design competition and using a chatbot

What we are going to do here is use the chatbot (that uses a Llama 2 model for output) in the way many folks are using it now - to find information and solutions to problems. We’ll do this in a guided way that contetualizes queries you’ll give to the chatbot with your design challenge. Throughout this, you’ll have an opportunity to see the code that is used to develop the chatbot system, or you might end up not worrying too much about the code itself and instead follow the minimum instructions to get input/output.

Either way, you’ll have this module to refer back to later if you want! In showing you “how the sausage is made”, we’ll also show you some methods folks use to augment their models with specific context and information so that they work better.

Ok, let’s get to setting up our model and running things! Navigate to the Guided Walkthrough to begin!